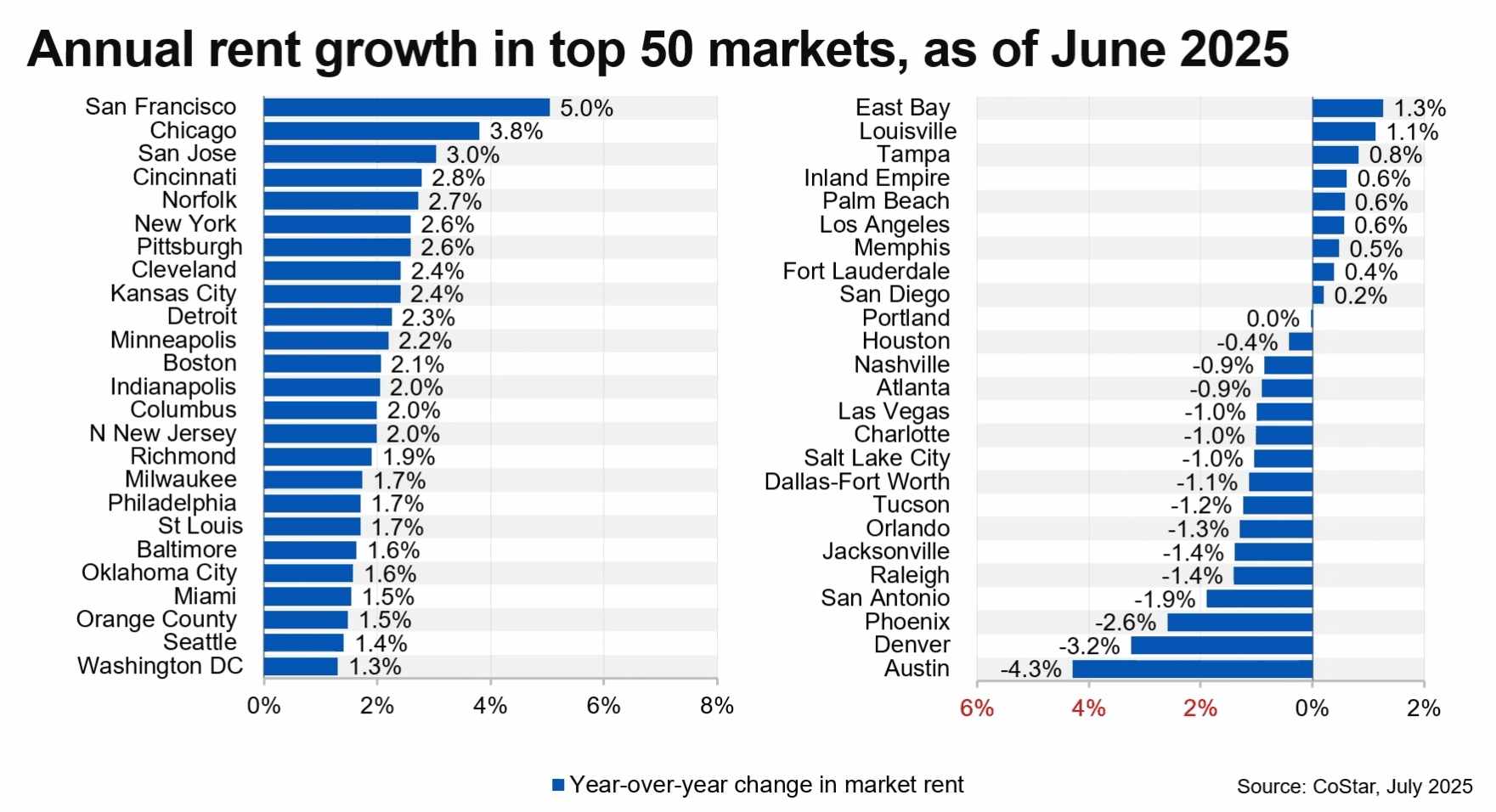

Among individual markets across the country, there’s a nearly 30 percentage point difference between the largest increases and the steepest decreases in rents over the pandemic. For example, Riverside/San Bernardino was the biggest beneficiary, with rents rising 9% over the past year. San Francisco, on the other hand, took the biggest hit, with rents dropping almost 21%.

And while such a wide range in performance among the nation’s metropolitan areas is one thing, the difference can be just as big among neighborhoods in any single one of those metro areas. In Washington, DC, for example, rents jumped more than 10% in one Virginia suburb but plunged 20% in a more urban neighborhood just outside of the District proper.

There are similarly large differences in performance among neighborhoods in and around big cities up and down the coasts. These gateway markets are seeing the greatest bifurcation largely because of significant weakness in their pricey, dense downtown areas, where square footage comes at a premium. Meanwhile, less expensive suburban neighborhoods are still doing relatively well, and apartment operators there are finding that they can still raise rents despite the challenges from COVID-19. Though it’s more pronounced in big gateway markets where the cost of living is high, this urban-suburban divide is a trend seen nationally, driving down prices for urban-dwelling apartment renters – even in the Sun Belt – and increasing pricing in the more affordable, less dense suburbs.

Across major apartment markets, Washington, DC saw the largest rent change disparity among its neighborhoods. Some of the deepest rent cuts in the nation were seen in the District-adjacent Crystal City/Pentagon City submarket, where prices have come down by 20% since the onset of the pandemic. In fact, while the market overall saw rent declines ease a bit in between January and February, this submarket saw declines get deeper. On the other hand, the suburban Fredericksburg/Stafford area of Virginia has seen notable rent growth of 10.5% since February 2020. Despite these performances, rents are still about $400 cheaper in Fredericksburg/Stafford.

In New York’s very expensive Financial District, rents were cut by 23.7% since the start of the pandemic downturn. Meanwhile, rent growth of 4.4% was seen in the Northern Suburbs of Orange and Ulster counties, which is the only New York submarket with monthly prices below $2,400. The range in monthly rents among neighborhoods in New York is the widest in the nation, with the expensive Lower East Side of Manhattan commanding rents that are $2,627 ahead of the least pricey Northern Suburbs. In between, the remainder of the very expensive Manhattan areas logged rent cuts between about 13% and 19%. On the other hand, the only other submarket in New York to see rent growth in 2020 was the Bronx, with an increase of 3.8%.

In Chicago, operators in The Loop cut rents by 18.1% in the year-ending February, while declines were also steep at 12.5% in the Streeterville/River North submarket next door. These are the two most expensive parts of Chicago, with monthly prices topping $2,000, and both have experienced steep occupancy declines in recent months. On the other hand, the Cook County-adjacent Merrillville/Portage/Valparaiso area – a northern Indiana suburb where rents are just over $1,000 – saw significant price growth of 9.3% in the past year.

While the rent change spread in San Francisco was pronounced, this market stands out for the fact that not a single submarket logged any rent growth during the pandemic. The deepest decline of 26.9% was seen in Downtown San Francisco, while steep cuts of more than 20% also registered in SoMa and Central San Mateo County. Marin County, north of the San Francisco Peninsula, saw the market’s best performance, but even then, there were cuts of 5.6%. Among the nation’s 50 largest apartment markets, only one other saw a complete absence of growth in 2020, and that was neighboring San Jose. The spread there was slightly less pronounced, with cuts of 22.8% in the worst performing submarket (North Sunnyvale) and cuts of 5.4% in the best (East San Jose). The range in monthly rents across the three Bay Area markets is relatively small at about $600 to $620 because even the lowest-priced submarkets are still expensive. Not a single neighborhood in the Bay Area rents out apartments for less than $1,900.

Atlanta’s story is the opposite of the Bay Area’s. The Georgia market was a top performer for rent growth overall during the pandemic, and its southern suburbs accounted for six of the nation’s 10 best rent growth performances in the past year. The best five showings in the nation were seen in Henry County (16.2%), Far South Atlanta Suburbs (14.8%), Southeast DeKalb County (14.5%), Stone Mountain (13.3%), and South Fulton County (12.5%). Atlanta’s Clayton County ranked at #8 in the U.S. with a growth of 11.4%. All of these top-performing Atlanta submarkets have monthly rental rates that are at or below $1,300. On the other hand, trouble spots in Atlanta are the more expensive urban core neighborhoods that have received lots of new supply over the past decade and rely on office-based employment. Rent cuts of roughly 1% to 3% were seen in Midtown Atlanta, Northeast Atlanta, West Atlanta, Buckhead, Briarcliff, and Dunwoody, where rents are between $1,400 and $1,800.

Among this group of metros with a 20 to 30 percentage point differential in neighborhood rent change levels, the average effective asking price difference is also sizable. On average, rents in the most expensive submarkets of metros in this group are $1,225 ahead of the least pricey areas.

But in many of the nation’s metros where the cost of living isn’t as high, neighborhood performances in the past year are more uniform. Among the nation’s markets with the least variation in neighborhood rent change – between only about 3 to 7 percentage points – the average monthly price difference among submarkets is much tighter as well. In this group, rents in the most expensive submarkets are only about $422 away from the most affordable.

Nowhere was rent change in the COVID-19 era more uniform than in Providence. Each submarket in Providence logged rent growth in 2020. The strongest (5.2%) was in Bristol County, while the softest growth (2.8%) was in the Providence submarket. The difference in average monthly rents between Providence’s most expensive submarket (Bristol County) and the least expensive (Providence) was only $84, the smallest in the nation.

Contributing to the narrow spread in Providence’s submarket performances and average rents is the absence of a true downtown in this Boston-adjacent metro. That’s a characteristic shared by many other markets having the smallest differences in neighborhood rent performances, including the Los Angeles-adjacent Anaheim and Miami-adjacent West Palm Beach. One could argue that two markets – Greensboro/Winston-Salem and Raleigh/Durham – have two lesser developed downtown areas across their combined metros.

Rent growth in Virginia Beach, also lacking a distinct downtown district, was one of the best among the nation’s largest apartment markets during the pandemic. This market also avoided rent cuts across all submarkets during the past year. Federal government jobs and private-industry defense-related employment that anchors the area helped minimize economic fallout in 2020, keeping occupancy and rent growth well above national and South region norms. The most solid rent growth here was in the Virginia Beach East, Newport News, and Hampton/Poquoson neighborhoods, with each seeing rents, climb around 6% to 8%. The softest showing was in Southern Norfolk, with milder growth of 4.1%. In Virginia Beach, the difference between the most expensive Chesapeake submarket and the least pricey Northern Norfolk is modest at $280.

Two other markets with a tight spread in neighborhood rent change levels – Greensboro/Winston-Salem and Las Vegas – were among the national top 10 for overall rent growth in the past year. In Greensboro/Winston-Salem, all submarkets saw rent growth between 4.4% (North Winston-Salem and North Greensboro) and 8.2% (High Point). Only one submarket – Burlington – garners rental rates that are above the $1,000 mark.

In Las Vegas, each submarket also saw rents grow during the pandemic, with an upturn of 8.9% in Sunrise Manor ranking as the highest, while the more expensive Southwest Las Vegas, Green Valley, South Las Vegas, and Summerlin/The Lakes all saw increases between 2% and 4% in the past year. The difference between rents in the most expensive submarket (Summerlin/The Lakes) and the least expensive (Central Las Vegas) is a little over $450.

Why has the presence of a downtown area affected rent change patterns in the metro so much throughout COVID-19? Urban core submarkets have been particularly impacted by job loss in the past year. Offices have closed and more employees are working from home, removing the location-specific attraction to downtowns. Additionally, when downtown bars and restaurants closed, professionals that had been previously attracted to the quality of life that urban cores afford started to dissolve their households – either by choice or because a laid-off roommate could no longer pay rent.

Further complicating those dynamics, urban core districts have seen intense apartment building activity in recent years, leaving these areas at a disadvantage during times of depressed demand. The already elevated construction levels in urban cores are scheduled to increase further, making full occupancy goals – and therefore pricing power – more difficult, at least until jobs return and workers go back into the office.

Source: How Has COVID-19 Affected Apartment Rents? It Depends on the Neighborhood | RP Analytics

Receive Market Insights

Periodic analysis on rents, pricing, cap rates, and transaction activity across Chicago and key suburban markets.